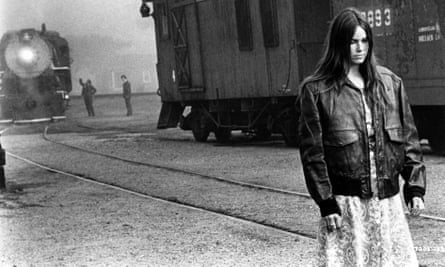

In the final scene of Martin Scorsese’s second feature film Boxcar Bertha, the luckless heroine, played by Barbara Hershey, vainly pursues the freight car from which her labour organiser lover (David Carradine) is dangling, having just been crucified by capitalist goons. The sequence foreshadows the scene in his 11th film, The Last Temptation of Christ, where Hershey, now playing the luckless Mary Magdalene, will again see her inamorata crucified. As before, he falls victim to goons.

An unsatisfactory love affair will result in a completely unexpected crucifixion in Gangs of New York – goons again – while crucifixions with no explicitly erotic subtext occur all over the place in Silence. I know all this because I just spent a month watching all 26 of Scorsese’s feature films – rewatching them mostly – and noticed patterns and themes running through his work I had not noticed before. From 1972’s Boxcar Bertha to 2016’s Silence, a solemn, autumnal film about overmatched Jesuits in 17th-century Japan, the message in Scorsese’s work is repeated again and again. Violence is a fact of life. In affairs of the heart, women almost always back the wrong horse. And if you keep messing with the wrong people, you’ll end up hanging from a tree.

Stylistically speaking, Scorsese found his footing early. After his 1967 debut, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, an arty black-and-white film starring Harvey Keitel, it was another five years before Bertha saw the light of day. But a year later his third film, 1973’s Mean Streets, also starring Keitel, was recognised immediately as a classic, a gangster film unlike any gangster film ever seen. As opposed to Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, released just one year earlier, Mean Streets did not make gangsters seem glamorous, resourceful or even intelligent. It made them look like screwups.

Mean Streets contains all the classic elements of a Scorsese film: a restless camera, tons of voiceover, waves of infectious pop music, a doomed love affair, lots of glitzy, ill-advised attire, a ferocious fistfight, witty banter between fun-loving partners in crime, and the looming spectre of murderous retribution. It also showcases both New York City and Robert De Niro, the twin linchpins of Scorsese’s career.

Stylistically, Scorsese’s films bear no relationship to classic Hollywood motion pictures. They are long (sometimes incredibly long), contain heaped servings of sadistic violence, and the good guys don’t win – because there aren’t any good guys. Just goodfellas. But in one area, Scorsese’s work is exactly like that of John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock and his other illustrious forebears: he built his career around great actors.

At first it looked as if he was putting his money on Keitel, but then De Niro showed up with his raw, anti-matinee-idol acting style, his amazing eye work, commanding attention in a way other actors could not. From Mean Streets onwards, De Niro, a brute, volcanic force of nature of a sort not seen since Marlon Brando, would appear in 10 Scorsese films, including his latest, Killers of the Flower Moon.

There have been other stars along the way: Leonardo DiCaprio, Jack Nicholson, Willem Dafoe, Paul Newman, Matt Damon and Daniel Day-Lewis. Not to mention Cate Blanchett, Ellen Burstyn, Liza Minnelli, Cameron Diaz and Sharon Stone. Scorsese rarely uses actors that do not fit. Tom Cruise in The Color of Money is one exception. Too much hair. Too many teeth. He makes you wish Joe Pesci – De Niro’s tough-guy sidekick in Goodfellas, Raging Bull and Casino – would stop by and pop the massively annoying Cruise in the chops.

Scorsese fills his films with cruel, rapacious men who have a rollicking good time until they antagonise the wrong people and end up getting shot, stabbed, hacked to pieces or buried alive. They are men about whom it can be said: “There’s something wrong with this guy.” De Niro’s cabby in Taxi Driver belongs in an institution. His flamboyant ex-con in Cape Fear should be sharing the adjacent cell. Also fitting the mould of the unapologetically sociopathic are the cool gangster De Niro plays in Goodfellas, the reptilian cop Matt Damon brings to life in The Departed, and any number of unappealing human beings incarnated by Joe Pesci.

There is also something not quite right about Dafoe’s confused, idiosyncratic Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ – the Bible makes no mention of Christ personally building crucifixes for the Romans – and the same is true of De Niro’s delusional wannabe in The King of Comedy. Most especially, there’s Day-Lewis’s scenery-munching, immigrant-loathing lollapalooza in Gangs of New York. There is never a point where anyone in the audience can actually identify with any of these people. Not unless they, too, have deep psychological problems.

Scorsese understands that moviegoers are essentially tourists: they want to get a glimpse of depravity but then retreat to the safety of their own humdrum lives. It’s not that Scorsese approves of the toxic masculinity that permeates his films. It’s just that toxic masculinity is a cornerstone of American life – and the public are fascinated by bad behaviour.

The world of Martin Scorsese is populated by bosom buddies who end up betraying one another (Goodfellas, Silence, Casino, Gangs of New York, The Last Temptation of Christ), and men who reflexively mistreat women (Raging Bull, The Wolf of Wall Street, Casino, Cape Fear). There are good parts for women in Scorsese films, and even big parts – Lorraine Bracco in Goodfellas – but for the most part, women appear on the undercard. They get knocked up, they get knocked around and, in some cases (Raging Bull), they get knocked out. This is no country for young women. As for Black people, there are a few roles here and there, but nothing substantial. In this universe, Black people are kept at the periphery of the mainstream narrative, just as they are in real-life America.

Scorsese has always painted on a vast, sprawling canvas, particularly when making films about vast, sprawling America. Casino is an epic, as are Gangs of New York, The Departed and The Irishman, all of which chronicle the rise and fall of criminal empires. But even Kundun, his unexpected Dalai Lama biopic, is epic in scale, though it lacks the thrills and spills of Scorsese’s trademark films. The only slight, lightweight movies Scorsese ever made are After Hours and Hugo. Even the elegiac The Last Waltz has an epic quality to it.

He has had few missteps. The bloated, self-indulgent New York, New York is no treasure for the ages and the eerie, gothic Shutter Island seems interminable. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore is an engaging film, but with its upbeat ending it’s an outlier in the Scorsese canon. And try as he might in The Irishman, despite computer-generated trickery, Scorsese cannot make De Niro seem as if he’s 30 years old, Irish or from Philadelphia. Be that as it may, the film gets the job done.

When Scorsese wanders away from his comfort zone, the results are mixed. Although it was a huge hit, the long, repetitive The Wolf of Wall Street doesn’t tell us anything about Wall Street we don’t already know: it’s filled with scum. Throughout The Wolf of Wall Street and The Aviator, the audience may again find itself wishing that Pesci (four films with Scorsese) would drop by and knock some heads around. Because even at their most larcenous, megalomaniacal or depraved, businessmen just aren’t that interesting. Movies about the guys with the six-guns are a lot more fun.

His films never let the audience take more than a few seconds off. Whether it’s the Rolling Stones’ Gimme Shelter (used in three films) or the intermezzo from Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana (heard in its entirety during the opening credits of Raging Bull), the soundtrack keeps coming at you, pounding you, shaping your emotions. The music, much of it suggested by Robbie Robertson (whose group, the Band, is the subject of Scorsese’s concert documentary The Last Waltz), tends to consist of enduring, time-honoured hits. As a result, the movies do not seem dated like so many films of the 80s, ruined by their appalling smooth jazz soundtracks.

If you don’t like overhead camera angles or voiceover, you won’t like Scorsese. The voiceover never stops in Goodfellas and the mega-weird Bringing Out the Dead, and in the fussy, mannered The Age of Innocence, it sounds as if Edith Wharton herself is doing the voiceover, reading material from beyond the grave. In Casino, even the minor characters do voiceover. It’s as if Scorsese doesn’t trust the audience to follow the story. Or maybe it’s just an easier way to make films.

There are only a few times in your life that you will find yourself in a cinema watching a movie that you already sense will become a classic. Rewatching Raging Bull, Taxi Driver and Goodfellas brought back that feeling for me. So did The Departed, a remake of the Hong Kong classic Infernal Affairs. If you really love movies – not everyone does – and you really love that feeling of seeing something you may never see again, Scorsese is your man.

From the start, Scorsese, with his dark, intense films, was swimming against the tide in an art form that would become increasingly frivolous and inane. Like Hitchcock, he made movies that no one else could or would make, and like Hitchcock he has routinely been overlooked by awards committees.

Scorsese does not make superhero movies. He does not make heartwarming movies. He does not make movies involving time travel. By and large, he makes violent movies about violent men who have a nice long run of success before fate catches up with them. He makes beautiful movies out of ugly behaviour. He’s been doing it for a long time and there is no reason to stop now.

Killers of the Flower Moon is in cinemas now.

"Movies" - Google News

October 21, 2023 at 03:15AM

https://ift.tt/QpeFZBI

My month with Marty: what I learned watching all 26 of Scorsese’s movies - The Guardian

"Movies" - Google News

https://ift.tt/UGvpChi

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "My month with Marty: what I learned watching all 26 of Scorsese’s movies - The Guardian"

Post a Comment