When army veteran, author and CEO Phillip Sheppard appeared on US reality TV show Survivor, he struggled with how he was presented. The 62-year-old African-American, who first emerged in 2011’s Redemption Island season and later in 2013’s Caramoan, says his portrayal on screen was very different from how he had perceived his actions. “I realised that what I thought I did in the game and what my memories were... the way it was edited, it was like... everything I did was delusional or crazy or didn’t have a purpose,” he says.

Sheppard says that in the past, many former black “Survivors” had unofficial discussions about how they were portrayed, and how to tackle the issue. Like Sheppard, many black contestants say they were stereotyped as aggressive. But some were also portrayed as lazy, as Ramona Gray Amaro – the first black woman who appeared on the show’s first season – told US broadcaster NPR last year.

According to Sheppard, the events of 2020 made them develop a sense of urgency. He’s now part of a group formed by black alums of the Survivor franchise, Black Survivor Alliance, who went public last summer about their collective concerns regarding their treatment over the years. “It wasn’t until George Floyd that everybody could no longer deny what they saw,” he says, referring to the high-profile police brutality incident that resulted in the death of the black Minnesota resident.

Though the reckoning was a long time coming, it’s unsurprising that this push for change is taking place now; a resurgence of Black Lives Matter amid racially motivated violence against black people has led to a surge in individuals and organisations addressing racism and representation in the workplace.

This includes the reality television industry, where some noteworthy attempts to rectify institutional racism are emerging. This genre, however, thrives on drama and conflict as an entertainment form, which sometimes involves taking advantage of bias and stereotypes. So, any attempt to prioritise equity is not just a matter of diversifying its representation; change is needed behind the scenes, and even to the entire model itself.

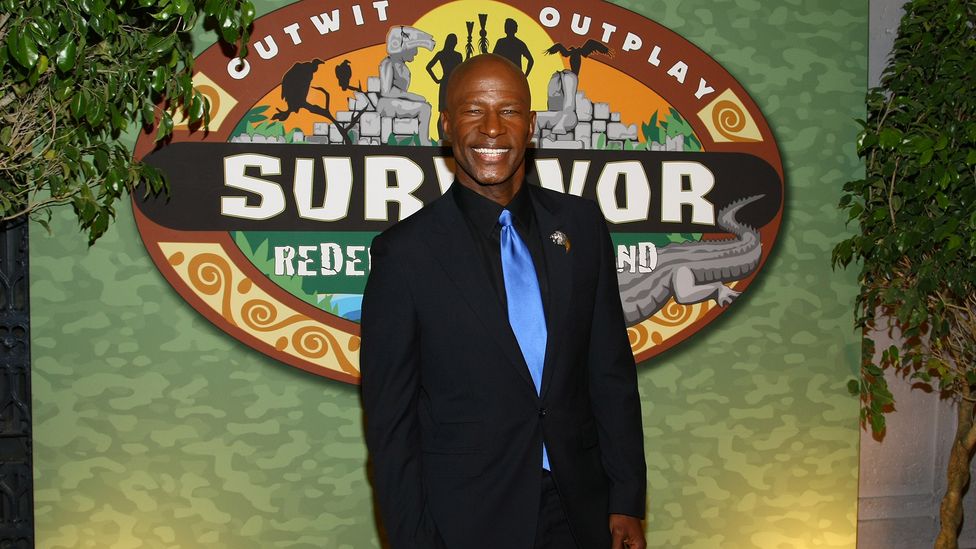

Phillip Sheppard competed on Survivor in 2011 and 2013, and is part of a black alumni group that's pushed for better representation on the US programme (Credit: Getty)

‘Not just who is represented, but how’

In November, a few months after Survivor’s black alums raised their concerns, programme-maker US network CBS announced a goal to ensure 50% of all casts in its unscripted shows are Black and Indigenous People of Colour (BIPOC). Back in August, Arisa Cox, host and executive producer of Big Brother Canada, also shared on Twitter that she would be aiming for “50% BIPOC on our next cast”.

NBCUniversal Television network’s Bravo TV, home to many popular US reality series, also put itself in the spotlight. Critics often cite many Bravo shows, including the famed The Real Housewives franchise, for perpetuating racism, featuring typecasts and caricatures. In Housewives, for example, casts are generally homogenised along racial lines, with only periodic introductions of cast members of a different ethnicity. There have also been explicit incidents of overt racism and racialised name-calling by white cast-mates toward castmates of colour, with seemingly few repercussions. Real Housewives of Atlanta, which features a majority black cast and is one of Bravo TV’s most popular series, has long faced accusations of racialised stereotyping in its production and presentation.

Rather than radically alter its model, Bravo TV baked a national conversation on race into parts of its programming. In August, the network offered a 90-minute TV special, Race in America: A Movement Not A Moment, in which stars from some of its shows held a roundtable to discuss race and racism. Two cast members on restaurant-based reality show Vanderpump Rules were also fired when incidents of racism and stereotyping of a former black co-star emerged. And, on its current Housewives shows, some cast members are now featured addressing Black Lives Matter on screen (though some fellow castmates and the fandom believe the discourse is disingenuous).

Of course, the problems of the reality TV industry, from underrepresentation to reinforcing stereotypes, are not divorced from television as a whole. From the very inception of American entertainment and pop culture, racist caricatures including blackface and portraying Asian-Americans and Latino-Americans as ‘foreign’ has been part of the medium. Yet unscripted television differs from its scripted counterpart because of how viewers experience it. To many viewers, reality TV feels real, and therefore the characters are relatable to our values and how we see ourselves. And, because the genre is broad, covering everything from dating to cooking to surviving in the wilderness, viewers can imagine themselves in many of the scenarios.

“Reality TV is a social construction and like all social constructions, we say as sociologists, it’s kind of slippery. The boundaries are kind of difficult to discern,” says Danielle Lindemann, a Lehigh University professor of sociology. In other words, these seemingly authentic scenes are still manufactured, and for underrepresented groups, the challenge of how individuals and groups are presented is an old media problem. More than underrepresentation, Lindemann is concerned with the types of representation people of colour receive, notably their depictions on screen and the kinds of shows they are featured in.

Kandi Burruss of The Real Housewives of Atlanta, a programme criticised as being problematic in the past, has spoken out on issues like Black Lives Matter in 2020 (Credit: Getty)

“There’s this kind of certain obsession within reality TV about nouveau riche women, and then particularly nouveau riche black women… There’s something the public enjoys about looking at black women who are successful… and making fun of them … and that’s something that has been historically true in our country,” she says. Lindemann specifically references Bravo TV shows and the Housewives franchise, but also points to American network VH1’s Love & Hip Hop franchise, focusing on the lives of a majority black cast in the music industry.

“I think it’s important to think of not just who is represented but also how they are represented,” Lindemann says. “It’s important to attend to that as well and not just say, ‘Okay, well, we’ve met our quota’.”

Diversifying production – and introducing ethics

One way to alleviate some of the more intricate issues regarding representation is to have more people of colour in production. In addition to CBS’ BIPOC cast goals, the network also said they would allocate “a quarter of its annual unscripted development budget” to BIPOC-led projects. George Cheeks, president and CEO for the CBS Entertainment Group, acknowledged the genre as “an area that’s especially underrepresented, and needs to be more inclusive across development, casting, production and all phases of storytelling”. But without statistics on its teams’ current demographics, linked to improvements at every level, the statement lacks specificity. (CBS did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

ViacomCBS, however, which owns both CBS and VH1 alongside other entertainment networks, launched a diversity and inclusion website that features the company’s coalesced workforce demographics. As of July 2020, 63.8% of the company’s domestic employees were white, while Asian-Americans, black or African-Americans and Hispanic or Latino-Americans made up 10.6%, 11.3% and 11.6% of the company, respectively. Of the company’s senior leadership, it’s notable that less than 25% identify as BIPOC.

Networks might consider borrowing from HBO’s Power of Visibility initiative, a campaign featuring the perspectives of craftspeople behind the camera, all of whom are from historically underrepresented groups. People of colour who are part of the production process can intimately inform the industry and the public at large on how they navigate their experiences and what they believe is needed during this push for more inclusion.

’Is it worth it?’

Still, despite these potential changes on screen and off, there are experts who think the major problem of reality TV is in its very design.

Helen Wood, a professor of media and cultural studies at Lancaster University, UK, says the overt racism or microaggressions people face in interactions are ultimately still embedded in the shows’ blueprints. Wood emphasises that reality TV doesn’t merely portray people, especially those in vulnerable groups, inaccurately; the designs of many shows inevitably include having microaggressions as part of the drama, which contributes to individual harm. “It’s not just representing diversity in problematic ways. It’s also intervening in people’s experiences,” she says.

In Wood’s view, increasing diversity behind the scenes in the long run isn’t good enough; the industry needs to reconceive the entire model, beginning with how formats are designed. Yet such an approach would likely alter what makes reality TV unique or enjoyable: the drama, and the subsequent righteousness or outrage we feel from onscreen interactions. Though she believes applying ethics and stress-testing throughout the process will better prepare participants for harmful situations, Wood says we have to confront an ethical question: “Is the drama worth the expense? What is it worth?”

Arisa Cox, host and executive producer of Big Brother Canada, says that the programme is aiming for a cast next season that's at least 50% BIPOC (Credit: Getty)

‘Changed how people view me’

These are questions without easy answers. After all, reality TV is brain candy for most of the audiences that watch it, and individual moral interrogations might be more than most are willing to do. Given its comparatively low cost and high return, it’s also unlikely that the industry is going away any time soon.

Kristen Marston, a Culture Director at Color of Change, an online racial-justice organisation, spends a huge portion of her time consulting in writer’s rooms. According to her, post-George Floyd, networks are more open to rethinking their processes. “We’re seeing studios and networks and execs really paying more attention and addressing the diversity on their sets... and we need to be providing [harm-reducing] tools on set and to our cast members,” she says. After 25 seasons, ABC's dating show The Bachelor has finally cast its first black lead, for example.

Yet while networks and programmes are rightly enthusiastic about initiatives, there remains an equally healthy suspicion among critics and experts as to whether the changes will be effective. Still, if the industry is truly invested in long-lasting alterations to its practices, and potentially to its model, there is an opportunity for a cultural shift. And if reality TV can prove the sceptics wrong, then given the symbiotic relationship it holds onscreen with culture offscreen, perhaps a wider culture shift is possible across many more industries.

When Phillip Sheppard looks back on his time on Survivor, he says he wasn’t reflected in a positive light at all in either season. “The editing I received fundamentally changed how people viewed me.” Sheppard says that his portrayal led to episodes of depression, for which he sought treatment.

Sheppard does believe CBS is on the right track, and echoes the network CEO’s statement on pursuing inclusiveness at all stages of production and storytelling. “Had what he articulated been the case the last 20 years and 40 seasons, there would have been no need to have former black contestants in different groups and individuals to speak to the issues of systemic, systematic, implicit bias and micro-aggressive racisms.”

"TV" - Google News

January 13, 2021 at 03:00PM

https://ift.tt/2XTRSWp

Can reality TV shows help lead the way for inclusivity? - BBC News

"TV" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2T73uUP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Can reality TV shows help lead the way for inclusivity? - BBC News"

Post a Comment